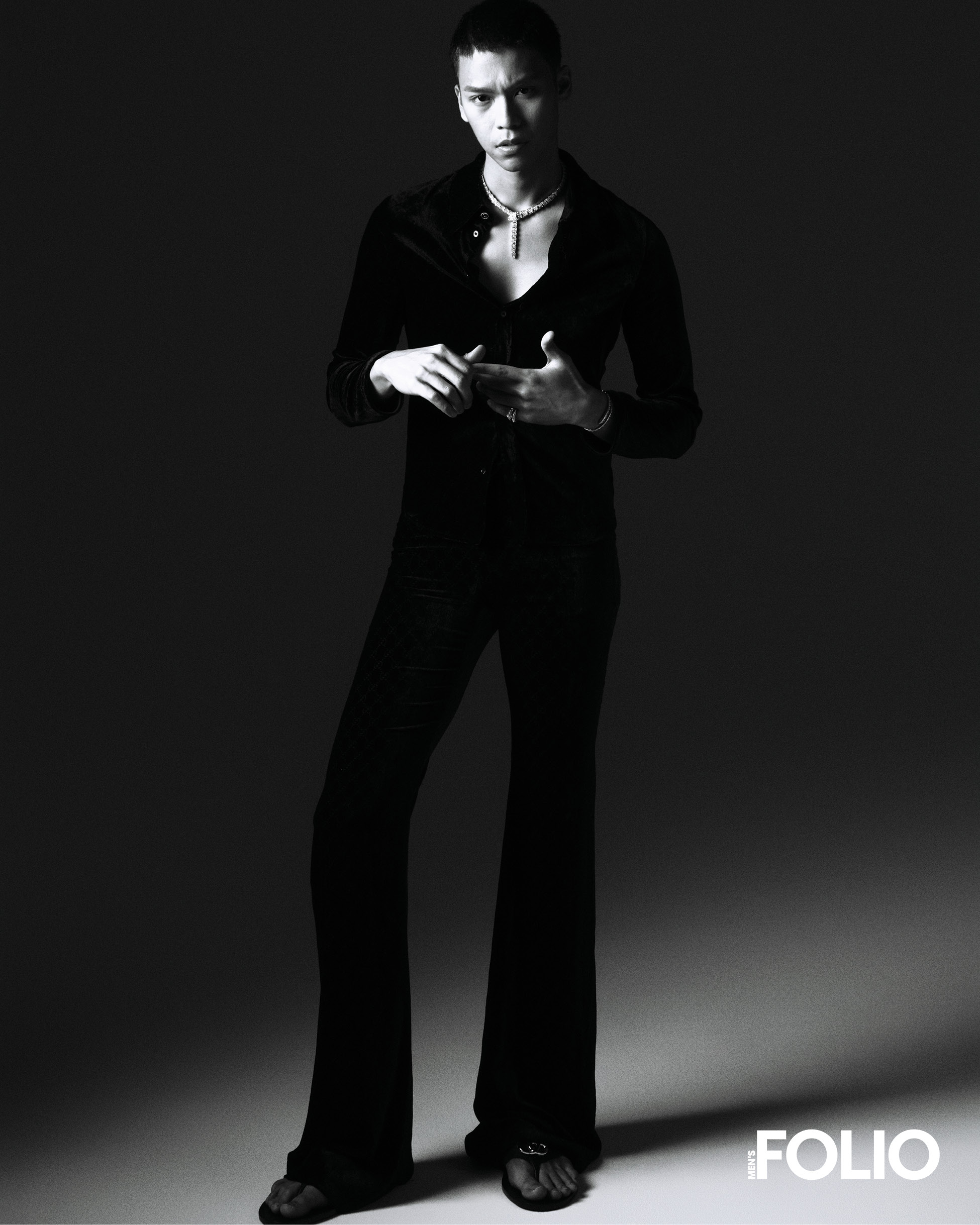

Mise-en-scène, French for “placing on stage”, refers to how every element — actors, space, light, props, and movement — in a single frame is arranged so that each detail plays a role to shape the story and emotion intended. A word rooted in theatre and film performance, yet Nadhir Nasar carries it through life, moving as if every moment is a frame to observe, sit with, and let unfold until it reveals itself.

Life, much like film, rarely offers complete explanations. It comes in fragments. “When you’re watching a scene, there are things you don’t understand straight away,” he says. “Sometimes the answer comes an hour into the experience. Other times it doesn’t, and you’re allowed to come up with your own answer.” Meaning, for him, is not something you chase — it will arrive when it’s ready. Presence matters more: noticing what is already there. “If you spend too much time trying to make sense of things,” he adds, “you forget to enjoy what’s happening on screen.”

Everything he says reflects the way he sees the world: like an audience member seated in a cinema. Even his moniker, Anak Wayang which loosely translates as “Child of the Show” or “Living Puppet” reflects that awareness. It carries the weight of performance, of observation, of moving between the person he is and the person the world sees.

Nadhir has a way of talking that makes two hours feel like ten minutes. A conversation with him rarely scratches just the surface. A question about work drifts into a memory, a lesson, a perspective you had yet to consider. For some, small talk is enough. For him, there is always a thought waiting to challenge the way you see.

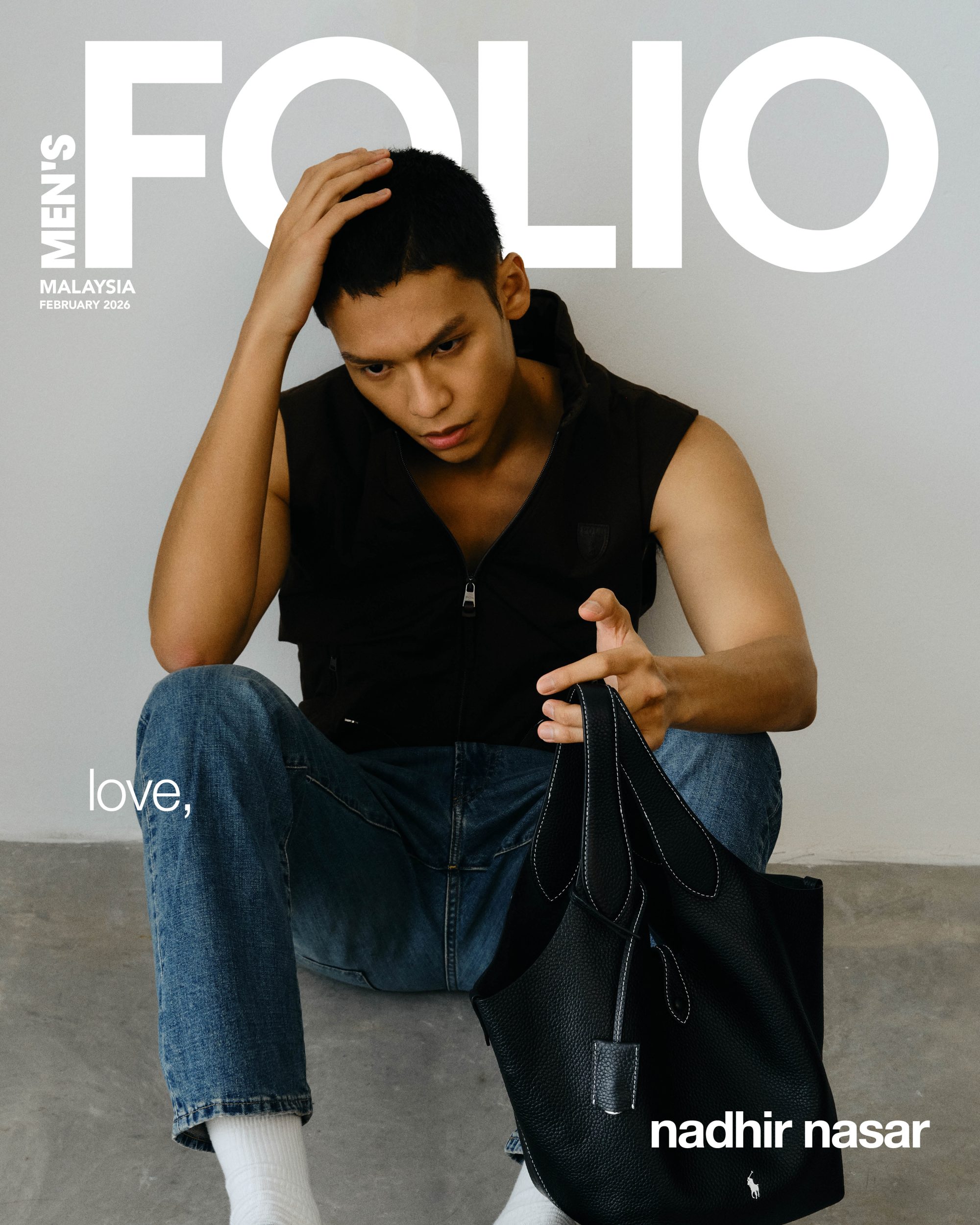

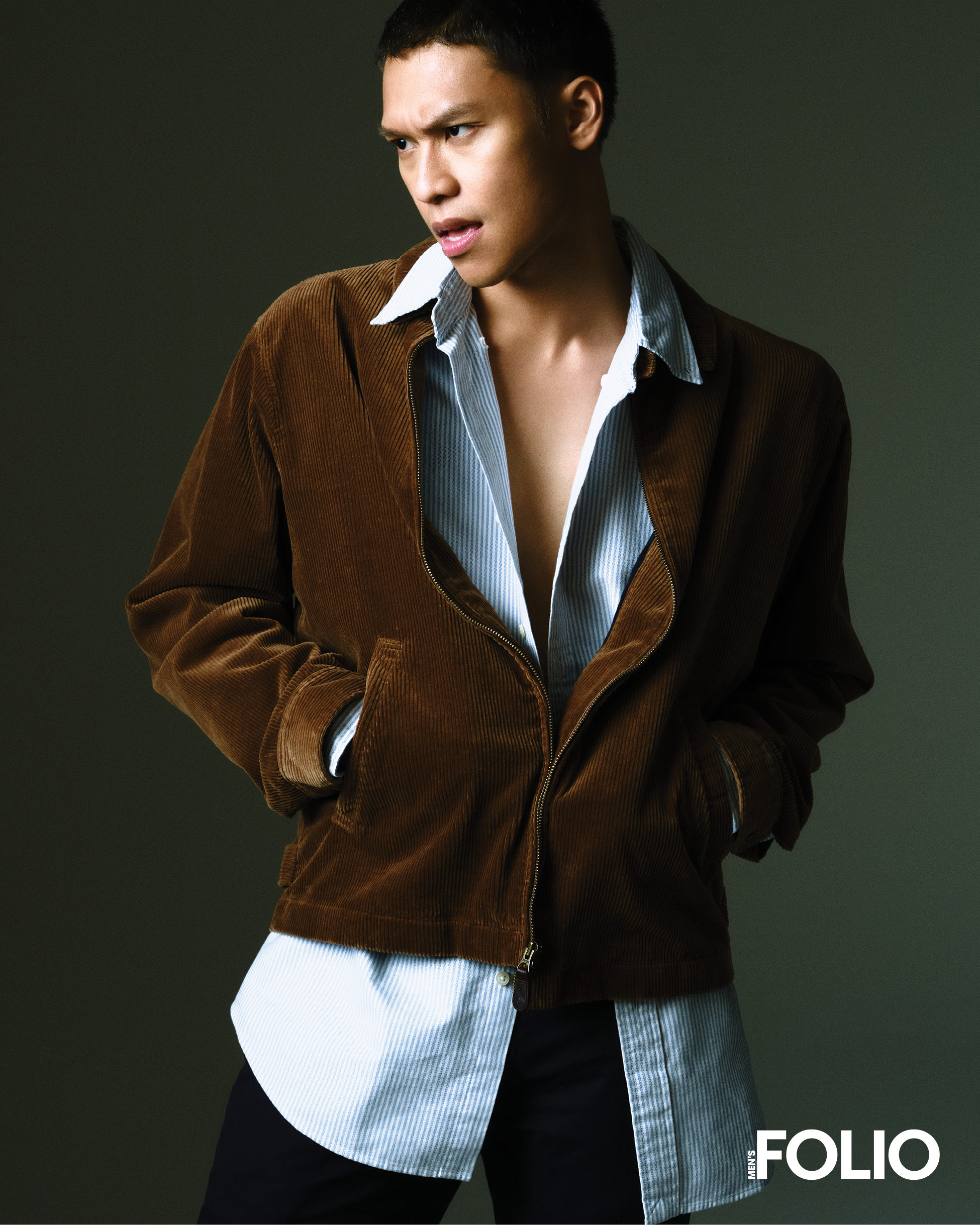

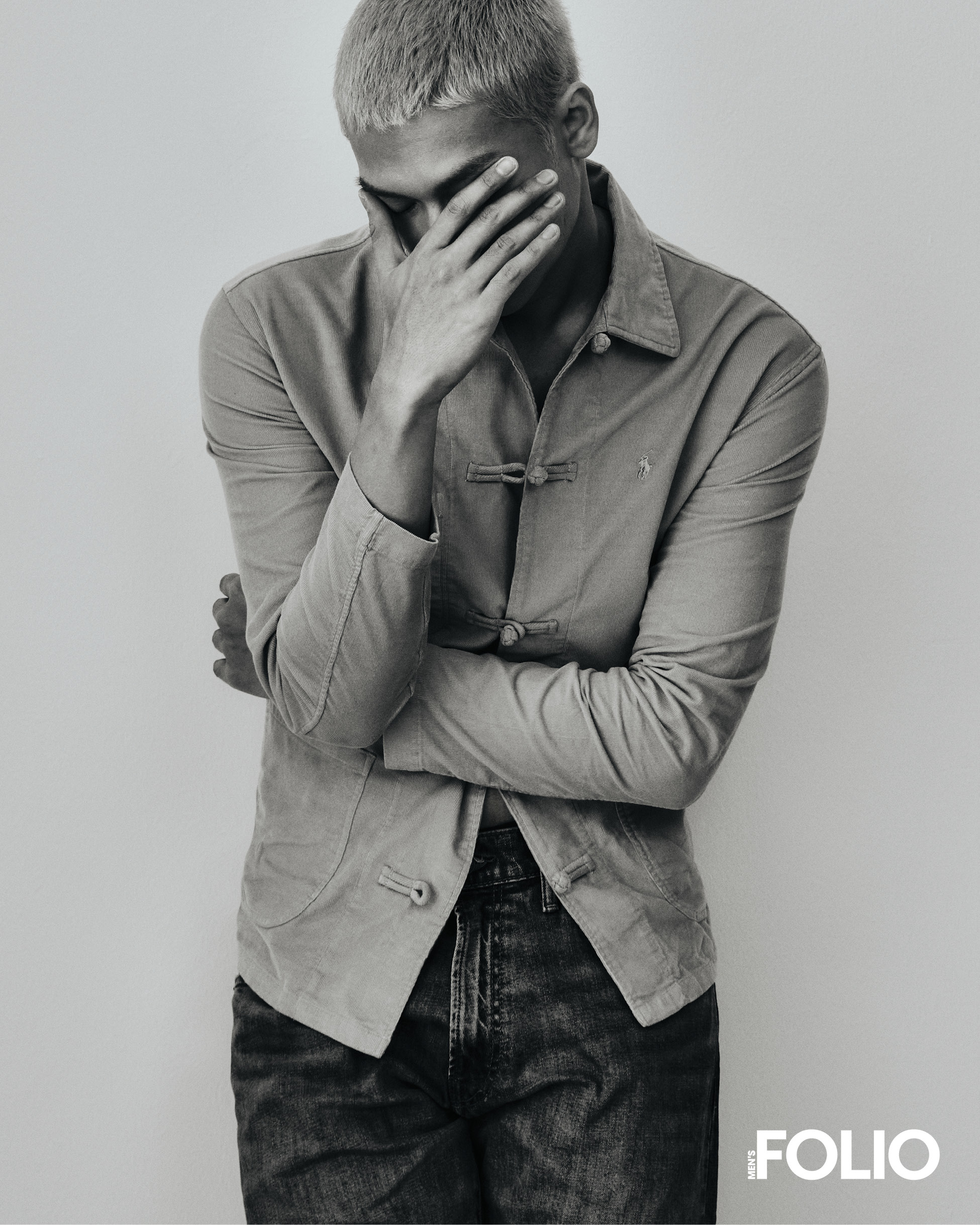

That same curiosity carries through his work with Men’s Folio, unfolding across three covers over the years. In 2023, he spoke to us about discovering himself through the characters he played. By 2025, the conversation had shifted to legacy — what it means to be remembered for his craft rather than for fame. Now, returning for February 2026 and stepping into his thirties, that reflection turns inward, as he rethinks what he values, both on screen and in life.

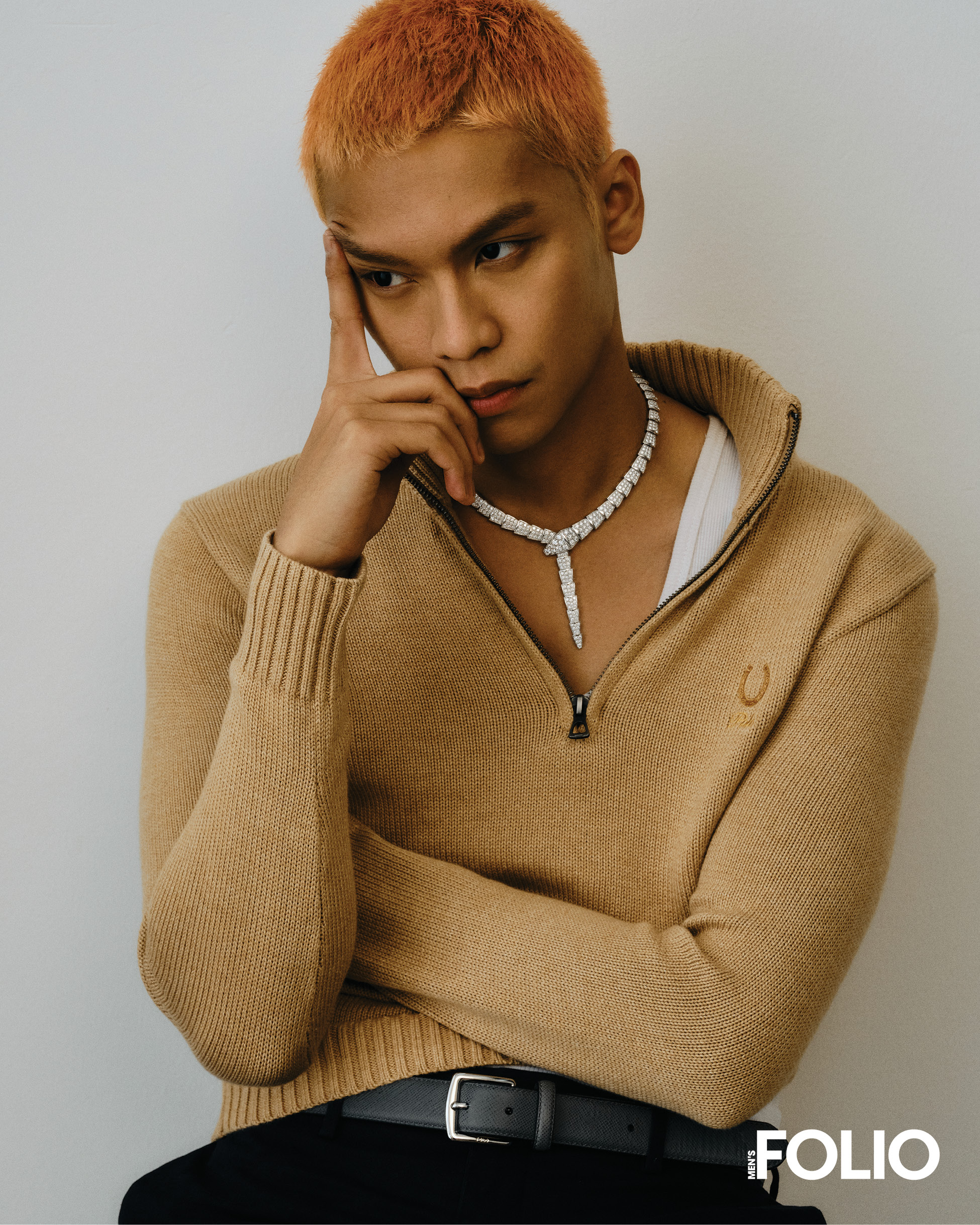

The first thing Nadhir mentions on set is his hair. Shaved into a buzz cut for Chelot, an upcoming action film where he plays an ex-military officer, it is a drastic change from the slicked-back wolf cut that had long been part of his public identity, from Hero Remaja (2020) days to playing Tahir in Pendekar Awang (2024). “I wasn’t feeling this hair at first,” he says. “My old hair felt close to who I am. I knew I looked good; I was comfortable.” As he sat with the discomfort, he made the choice to let these feelings go. Turning thirty, he has been reflecting deeply on what mattered, especially his self-perception of beauty. “Even if I look different for a while, so what? It’ll grow back.”

Like many who have grown tired of chasing perfection in a world where everything is endlessly polished, he seems interested in allowing a little imperfection. He is not afraid to admit that he has turned down roles that required him to shave his hair. “But now feels like the right time,” he says. “It would feel fake to say I like experimenting if I don’t even dare to change my hair for a character.”

On the subject of preparing for a role, we asked Nadhir what he thinks of method acting — the immersive technique where actors embody their characters beyond the camera. In recent years, the conversation has intensified in Hollywood with extreme examples: Jared Leto staying in character as the Joker on the set of Suicide Squad (2016), sending disturbing gifts to co-stars and insisting on being called Mr. J, or Leonardo DiCaprio enduring physical hardship for The Revenant (2015), from eating raw meat to sleeping inside animal carcasses. These cases often raise the same question — at what point does dedication become self-erasure?

For Nadhir, the answer is balance. “A good actor is still a good actor when they know how to separate who they are from who they’re playing,” he says. “Once the camera stops rolling, if you can’t tell what’s real and what’s not, you’re not mentally prepared.” Having portrayed characters far from his own experience — a man on the autism spectrum, an abusive husband, a struggling brother — he admits he is instinctively drawn to roles unlike himself. Not to lose himself, but to understand other worlds. Still, he’s clear about the risk: without grounding, it’s easy to forget who you are beneath the character.

“Even outside of acting, I’ve always been consistent in knowing myself,” he adds. “Who’s to say I can’t tap into a certain emotion just because I haven’t lived in that mood for weeks?” For him, mastery should not come from suffering, but from skill. Experience informs the work, but technique carries it.

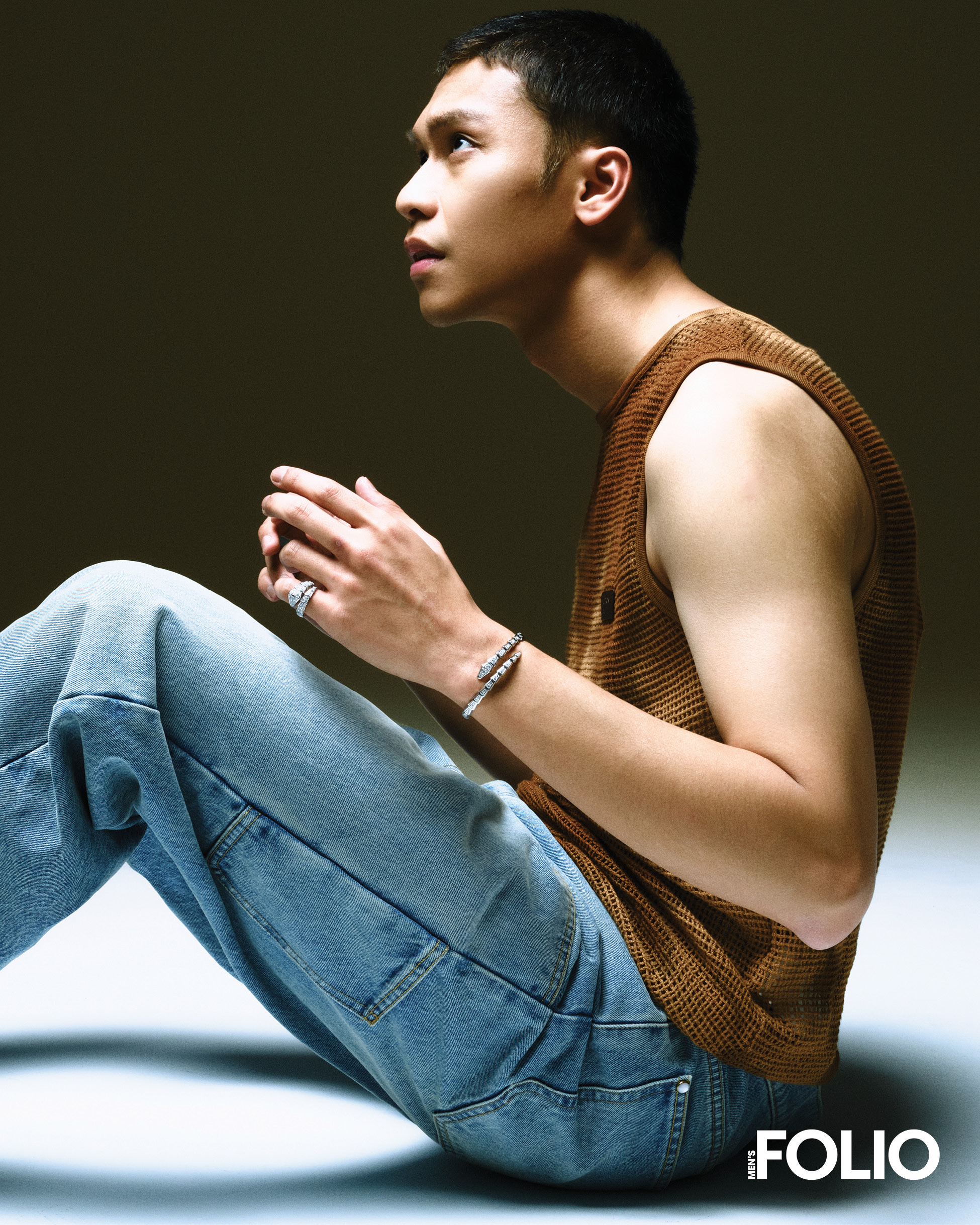

Nadhir’s grounding, he says, comes from family. “They remind me of who I am. No matter how many characters I step into, being with them always brings me back to myself. I’m very attached in that way.” This year, he has realised just how deeply he cherishes that bond.

That realisation came after watching Aftersun, a film about revisiting childhood memories with a parent long after those moments have passed. It stirred a melancholic reflection on his own upbringing, and the slow understanding that parents are human too, with their own struggles.

“It made me think about getting older, about my parents facing their own challenges. Sometimes it makes me sad, missing moments that feel further away each day. But I’m grateful that I’m still creating memories with them now. It’s bittersweet.” Inspired by this, he now commits to two family vacations a year, a way of staying present and holding on to the time he still has.

Despite this pick, his usual film choices lean in another direction. These days, everyone seems to reveal themselves through their Letterboxd top four. Nadhir’s selection leans toward big, fantastical worlds: The Dark Knight (2008), Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005), It (2017), Wonka (2023). “I love fantasy,” he says. “Stories that feel far from reality, with exaggerated worlds and characters. I like films that feel like an escape.” Watching movies as an actor can be difficult — he sometimes finds himself analysing performances or production. “But Hollywood films are made on a big scale because they’re for a global audience. I hope Malaysian productions can reach that level one day. Maybe through a Netflix series or a film. I believe in that.”

When it comes to local cinema, his taste is more intimate. His favourite is Talentime (2009), Yasmin Ahmad’s final film. “There’s something about how she captures love and grief. Watching it through a Malaysian lens makes it feel personal.” He believes the local industry needs more stories that reflect lived experiences and cultural nuance. “People miss Yasmin because her films felt honest. As I move into my next chapter as a director, I hope to bring stories about our people to the screen.”

Nadhir has spent 8 years of his twenties understanding the craft of acting, which he continues to refine. But in this new shift — putting his toes into filmmaking — he realises that the goal remains the same across everything he does: connecting with people, whether through work, conversations, or the relationships he keeps.

“If you ask me what I want across everything I do,” he says, “it’s to be meaningful — in my work, in my conversations, and in the relationships I keep.”

As February becomes the month everyone speaks about love, it’s worth remembering that it exists in all forms, outside of romance. Love can be for family, for craft, and for the people you choose to create for. And when growing up sometimes makes everything confusing, perhaps the best thing is to do what Nadhir does: watch it unfold, like a scene, next to the people who matter most.

Production Crew Credits

Photography Chee Wei

Creative Direction & Styling Izwan Abdullah

Interview Asha Farisha

Grooming Rachel | Plika Make Up

Hair Keith Ong

Fashion Coordination Liew Hui Ying

Photography Assistant Szen Cheah

Styling Assistants Alexander Cassius, Aqeil Aydin

Once you are done with this story, click here to catch up with our latest issue.