When Jonathan Anderson’s debut for Dior Spring/Summer ‘26 men’s collection drew a standing ovation, it was not because he reinvented the wheel. It was because he reminded people that fashion could still make them smile. Amid seasons dominated by minimalism and monochrome sobriety, Anderson’s collection landed like a sigh of relief: exuberant, sculptural, poetic. It was a declaration that menswear does not need to take itself so seriously to be taken seriously.

In a moment when everything from streetwear to suiting feels systemised, the idea of dressing with emotion almost sounds radical. This contrast becomes especially evident in the current menswear landscape, characterized by a focus on clarity, featuring clean lines, earthy tones, and understated luxury.

Even rebellion looks rehearsed, reflecting the prevailing mood. Archive fashion, too, sits at its peak; however, the internet often frames it through a more austere lens. As a result, designers such as Raf Simons, Helmut Lang, Hedi Slimane, whose restraint and severity have come to define the genre, continue to shape public perception.

But the designers long associated with emotional nuance and oddity did not disappear. Comme des Garçons continues to challenge proportion with playful irregularity. Yohji Yamamoto still explores imperfection as elegance. Galliano remains committed to theatrical storytelling. These designers are right there, alive and ongoing, yet men often treat them as distant curiosities rather than living sources of inspiration. Between reverence for the past and fear of the new, the desire for whimsy feels less like nostalgia and more like survival. It is a reminder that fashion is supposed to move you.

Yet that sense of play, so alive on the runway, rarely survives outside of it.

The men who consume fashion most intensely, who study runway archives and can identify Ann Demeulemeester’s late 90s menswear at a glance, are often the ones who dress with the least imagination. Their outfits lean on designer simplicity that conceals more than it expresses. They know the references but not the instinct behind them. They praise experimentation online yet arrive in uniform: the perfectly fitted plain tee, bootcut jeans, the way their pants meet their boots at the ankle, each proportion rehearsed into invisibility. Where did the joy go?

This is the contradiction that defines menswear today. The industry celebrates play while its most devoted followers police themselves into restraint.

A Return to Risk

For a generation raised on social media, fashion has become less about feeling and more about optics. To look composed has become the highest compliment. Call it aura farming: the careful cultivation of mystique through detachment.

Across men’s fashion online, sameness prevails. The styling may differ, but the instinct is identical: to look measured, controlled, untouchable. These looks are praised for their restraint, yet they are the most curated of all. They are not about getting dressed. They are about performing the idea of someone who does not need to try. It is the algorithmic version of detachment, an outfit optimised for mystique.

Men do not fear fashion itself. They fear what engaging too deeply with it might imply.

Online, that fear takes on a moral edge. Style is judged not only by appearance, but by whether it feels authentic. The internet rewards nonchalance and punishes visible effort. To care too much is to risk irony. The result is a strange hierarchy where detachment becomes the new sincerity. It is no longer enough to dress well. You must look as if you barely noticed.

The panic of appearing feminine, the fear of looking foolish, persists even among those who champion creativity. Coolness becomes armour. Not style, but self-protection.

Relearning How to Play

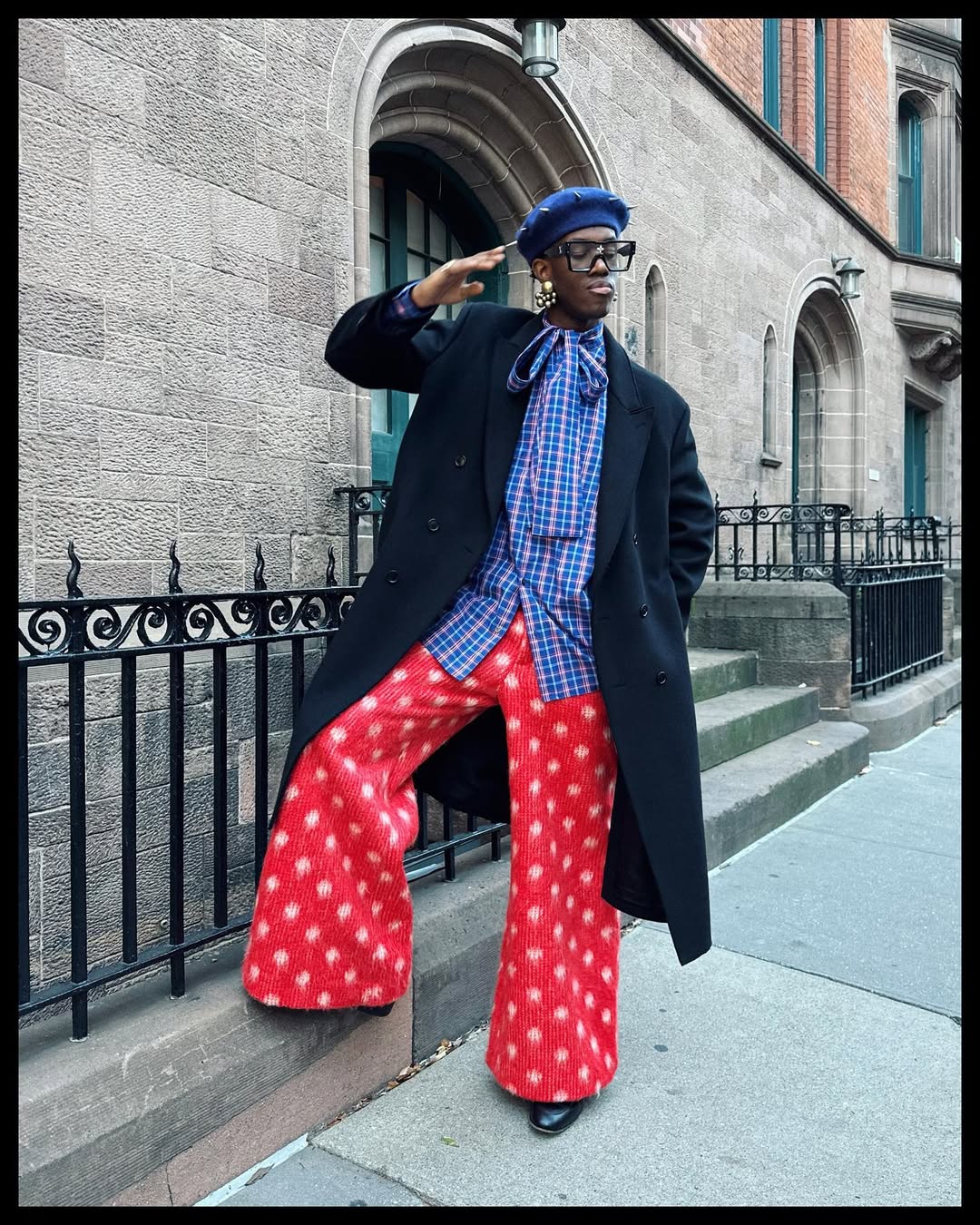

But history has always offered another path. Yohji Yamamoto wrote in My Dear Bomb that true style lies in contrast: to pair the polished with the playful, the refined with the foolish. It sounds contradictory, but that’s the point.

“It is always best to add something playful to any polished, coordinated look in man’s clothing. Attractive, classy, and chic alone result in something dull. The man with a real sense of style will always combine a highly polished look with something less refined, thereby combining the sensibilities of the man about town with those of the country buffoon, mixing the sensitive with the clownish. It simply will not do to have it all be of the highest refinement.”

The buffoon, for Yohji, is not an idiot. He is free. He is the man who dares to look slightly absurd and, in doing so, reveals taste as instinct rather than rule.

Thom Browne has built an empire on that tension, the disciplined and the ridiculous. His miniature suits, pleated skirts, and varsity theatrics are control exercises undone by humour. Craig Green softens utility into emotion. His Spring 2026 collection reworks uniforms with bedsheet prints, floral appliqués, and sculptural eyewear, turning workwear into something tender and strange. It is whimsy grounded in intention, not flamboyance.

Simone Rocha lends lace and volume to men’s silhouettes without irony, crafting emotion into structure. Anderson, for his part, understands that refinement does not need to erase curiosity. His Dior debut did not reject masculinity; it widened it.

On the runway, whimsy thrives because designers trust that audiences will understand the intent. Off the runway, that same instinct feels unsafe.

The Fear of Feeling

Whimsy is so often misunderstood. It is not kitsch or clownish proportions. Whimsy can be quiet: a crooked collar, a twisted seam, an exaggerated shoulder that throws balance into motion. It is humour in proportion, not parody.

Masculinity has long been tied to restraint and composure. To feel too much, or show too much, was to risk softness, and softness has never been easily forgiven. In a world obsessed with the perfect fit, whimsy is what makes fashion breathe. It is the crease that humanises the silhouette, the odd detail that reminds you that clothes are worn by people, not mannequins.

Fashion has always been a conversation between control and play. Right now, control is winning. The internet rewards polish: neutral tones, digestible formulas. Good taste has become synonymous with predictability.

Yet the best style moments always carry a flicker of risk. The ruffled cuff, the wrong shoe, the unexpected clash. It is not rebellion for rebellion’s sake. It is personality asserting itself against the algorithm.

The fear is not aesthetic. It is emotional. Play invites the possibility of getting it wrong, and for many men that vulnerability feels unbearable. A mismatched colour, an eccentric silhouette, a gesture that reads as too much all become opportunities for ridicule. So men retreat to safety, mistaking caution for taste.

Self-consciousness is not the same as self-expression.

To enjoy clothes too much is to risk credibility. But in protecting themselves from judgement, many men have stripped the style of its soul. As Yohji’s buffoon reminds us, the very thing that embarrasses you is what makes you interesting.

The runway offers permission. Everyday life demands courage. Dressing with whimsy today is not rebellion. It is a relief. A loosening of performance. A return to expression rather than approval. Because perhaps the point is not to look untouchable anymore. The point is to look alive.

Menswear has never lacked imagination. It has only lacked permission. Designers continue building worlds where humour, emotion, and elegance coexist, yet men remain spectators to their own liberation.

Maybe men are not afraid of whimsy at all. Maybe they are afraid of being misread for caring. Whimsy asks for participation. It invites you to care, to risk, to play. And sometimes the bravest thing a man can do is wear something that makes him smile. In a culture obsessed with control, that might be the most radical act of all.

Once you are done with this story, click here to catch up with our latest issue.